Fashion Patterns and Trade Marks

Monopolising mesmerising prints

Patterns can signify historical status, such as tartans which are only worn by particular families, encapsulate a joyous spirit such as the one symbolised by a simple polka dots design, or exude an aura of luxury captured by the infamous “Burberry check”.

Fashion patterns as trade marks

There are different avenues for protecting a pattern as intellectual property (IP). One of the most powerful forms of protection is that of a trade mark registration, which is a uniquely strong type of IP.

In the UK, it is possible to register a pattern as a trade mark. A pattern mark is a sign which consists exclusively of a set of regularly repeated elements.

Pattern marks can be applied for in relation to any products or services, although most commonly they cover clothing, fabrics, handbags and furniture.

However, unique difficulties may have to be surmounted before a registration can be granted.

One of the key requirements for registration is that a pattern must be deemed distinctive. In other words, it must be capable of being used by consumers as a means of distinguishing different traders.

This requirement applies to all types of marks. However, it may prove particularly complicated for patterns and prints, as consumers are not necessarily used to interpreting these as indications of trade origin.

Patterns that are commonplace, very simple, or traditional will lack distinctive character. For example, simple flower devices or ordinary polka dots.

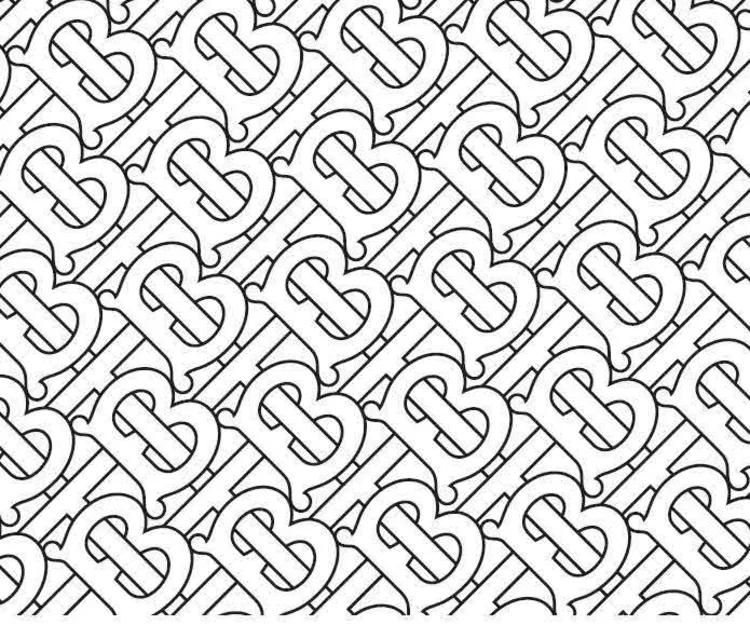

On the other hand, if a pattern is more unique and departs from the norms of the fashion sector, it is, generally, more likely to be used by consumers to distinguish between traders. For example, the pattern on the right is a registered UK trade mark owned by Burberry Limited.

Alternatively, if a pattern is not held to be inherently distinctive, well-known fashion brands may explore how to prove that their pattern has come to acquire distinctive character as a result of its use in the relevant territory and market.

A trader may be able to show that they have been using their pattern to educate consumers that it denotes their commercial source.

This avenue was tried and tested in the recent General Court decision T-275/21, Louis Vuitton Malletier v Norbert Wisniewski, where the fashion house Louis Vuitton tried to convince the court that its Damier Azur pattern (a chequerboard pattern unique to Louis Vuitton pictured here) had acquired distinctive character through use in the EU.

Unfortunately, on this occasion the court was not convinced by the evidence presented that the fashion house had used the mark throughout all the relevant countries so as to educate consumers of the pattern’s trade meaning.

Flags, tartans and shamrocks…

Designers need to also tread carefully when using signs that consist of or contain specially protected emblems or symbols.

It seems that the use of the Union Flag in print designs in the United Kingdom has never been more attractive to the public eye, and yet caution should be exercised when making use of potentially protected symbols.

Article 6ter of the Paris Convention prohibits the registration of certain signs as trade marks, or elements of trade marks, without the authorisation of the competent authority.

This includes State emblems such as flags and hallmarks, among other official signs.

Marks which consist of or contain a representation of the Union Flag or the flags of England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland or the Isle of Man, cannot be registered if it appears that the use of the mark would be misleading or grossly offensive.

However, stylised representations of the UK national flags may qualify for registration, depending on other factors such as the nature of the design and the products or services provided under the mark

For example, the following sign (UK trade mark registration No. UK00002617973) has been registered by the UK IPO in respect of clothes, among other products.

Another protected emblem is the shamrock – the beloved symbol of Ireland - which cannot be registered as a trade mark without the consent of the Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment in Ireland.

Virtual Goods and NFTs

As with many other businesses, fashion labels have recently turned to the digital world to expand their marketing horizons.

Just as with physical goods, digital goods can be included in a trade mark application in the UK and the EU.

Both the UK IPO and European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) have recently published guidance on the ‘classification’ of virtual goods in a trade mark application.

However, difficulties remain for pattern marks.

On 8 February 2023, the EUIPO partially refused Burberry Limited’s application for its maroon and beige chequered pattern for downloadable and virtual versions of clothing and footwear products.

It objected on the grounds that the pattern lacked distinctiveness for these particular products.

In contrast, the UK IPO accepted an application for the same pattern in the UK, in relation to virtual versions of clothing and footwear products.

Register as a design?

Of course, there are alternative methods of protecting patterns. One of the most popular ways is as a Registered Design.

A Design Registration lasts five years in the UK, but may be renewed for up to a maximum of twenty five years.

This is a much shorter right than that of a UK trade mark which may enjoy perpetual protection, subject to renewal.

Fashion houses releasing limited collections may benefit from this avenue of protection.

Designers may obtain Design Registrations for the patterned appearance of their products, for example for the patterns that appear on shoe soles, as shown below, or handbag prints.

Design Registration No. 90019236810004

Design Registration No. 90016791680019

A step in the right direction?

As our world’s fascination with eye-catching patterns continues, fashion brand owners can use various legal pathways to their advantage.

Alongside trade marks and design rights, copyright can also be used to safeguard patterns as artistic works and can be registered in certain countries such as the US.

All in all, the legal terrain may prove quite complicated to navigate but the prize at the end remains immensely lucrative for fashion labels.

Learn more about protecting your IP:

Authored by Karolina Fryzlewicz, a trainee trade mark attorney at Mewburn Ellis

karolina.fryzlewicz@mewburn.com